For punters, it is a pilgrimage. The Galway Races is seven days of racing, alcohol and bets. For the first time in 40 years, veteran bookmaker Francis Hyland was not this year part of the Galway bonanza. Earlier this summer, he sold his pitch at the racecourse, one of 98 at the festival. He says he sold it cheaply for €10,000 — “others are looking for €16,000,” he claims — yet he felt it was time to move on.

“It just became too much,” he says of the annual trek west. He drove up and down to the course each day from Dublin, setting off early and arriving home late, to save money and avoid the city’s pricey hotels. Selling the Galway pitch was part of a decision to “semi-retire”. Hyland now plans to limit his bookmaking activities to racetracks in Leinster. He also sold pitches at tracks in Kerry and Tipperary last year.

Despite the annual hoopla surrounding meets such as Galway, Hyland’s profession has been decimated by the decline of horse racing in Ireland. He estimates that the number of on-course, or rails, bookmakers has halved in the past 10 years. Betting at racecourses nationally has fallen from €214m in 2007 to just €67m in 2015. The staggering decline is a function of falling attendances, recession and the move toward online and mobile betting. Galway has not escaped. On-course betting at the track’s 12 days of racing was €27.5m in 2006; in 2015, it was €10.9m.

In the first half of this year, course bookmaker bets fell a further 9.8%. “Racing has challenges right through the whole system,” says Hyland, a board member of Horse Racing Ireland (HRI). “Attendance is down, sponsorship is down, national TV coverage is down, [the number of] owners are down.”

In 2006, almost 217,000 people attended the Galway festival. Last year, fewer than 150,000 came through the turnstiles. Attendance is down across the sport by a quarter in the past decade. It did rise in the first half of this year — by 1%.

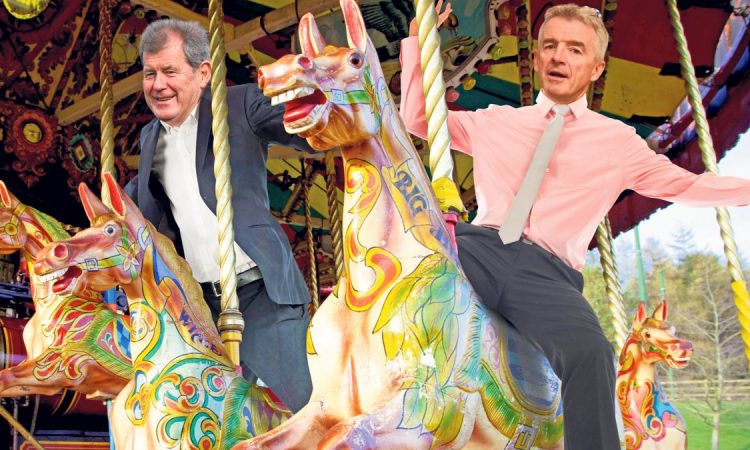

The number of owners has also declined sharply. Two individuals, the financier JP McManus and Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary, dominate the national hunt game. Between them, they sent 1,200 runners to post in the national hunt races here last year. In last Wednesday’s Galway Plate, the feature race of the festival, O’Leary owned eight of the 22 runners. The strategy worked, with outsider Lord Scoundrel squeaking home.

Flat racing is heavily dominated by a clutch of wealthy owners such as John Magnier, John Tabor, Derrick Smith, the Maktoums, the Aga Khan and the Haefner family. Yet even the wealthy have felt the pinch. The contribution of owners to the prize pool at the Curragh, for example, has fallen from €7m in 2006 to €3.8m last year.

Thankfully for racing, it has a one devout supporter: the taxpayer. The Horse and Greyhound Racing Fund received €68m last year, and funnelled, through the auspices of HRI, more than half that stipend into prize money. HRI cash accounted for 52% of all racing prize money in 2006, and 66% last year. Despite the sport’s declining fortunes, the fund was increased by €6m in last year’s budget.

If anything, state support for racing is likely to increase. HRI has established a €100m Racecourse Capital Development Fund to bankroll upgrades across the country’s 26 racecourses. (Britain with a population more than 10 times larger, has just 59 courses.) The fund is granting €2.5m to Punchestown, one of three courses in Co Kildare, with a spring festival that now challenges Galway as the country’s most successful. Yet the biggest outlay will go towards the redevelopment of the Curragh racecourse in Co Kildare, the home of flat racing.

A new company, which will own the racecourse, has been set up to oversee the planned €65m development. Curragh Racecourse will be one-third owned by the wealthy owners who control flat racing here. The venture will be headed by Derek McGrath, who formerly ran the Dublin head offices of European Rugby Cup.

“It’s a nationalised industry, funded almost entirely by the taxpayer, to subsidise a plaything of billionaires,” said one long-standing critic. The counter- argument is that racing is the showcase of a world-class thoroughbred industry, and prize money is the life blood of racing.

A nationalised industry, funded almost entirely by the taxpayer, to subsidise a plaything of billionaires

Senator and businesswoman Mary Ann O’Brien is a strong advocate. In an Oireachtas debate on the HRI’s budget increase last November, she dismissed complaints of elitism. She had attended a Goffs bloodstock sale on the morning of the hearing. “It is no more elitist than Billy the Bear,” she said. “On Monday, we sold a foal for my parents, who are in their nineties, for €4,500. [A] man who has worked for us for 30 years sold a National Hunt horse that won a bumper, which he had built up with a local man in point-to-points, for €140,000. That is like a lottery win for him.” In backing the racing fund, “we are supporting the rural economy”, she said.

Sean Barrett, a Trinity College Dublin economist and senator, once noted that the amount of money given to HRI was “twice the amount given to human sport” through the Sports Council. The payment of “€36 for everybody who goes to a race meeting” was an incredible level of subsidy, he added.

The economist Colm McCarthy, in his report on public expenditure dubbed An Bord Snip Nua, was also critical. The level of prize funds distributed annually in the UK is approximately 2.7 times that paid out in Ireland, but attendances at races are over four times those in Ireland. He suggested a €16.4m cut in the racing budget.

Though the horse and greyhound fund did fall to €54m for 2014, it is now restored, higher than ever, to a level of €74m.

The most vocal opposition to the size of the fund has come from high-street bookmakers, who are generally fingered as the section who should be paying more to fund racing in this country. Betting tax, at 1%, raised €26m last year. The extension of the levy to online betting is expected to raise a further €19m in the current year, still leaving the exchequer well short of the €74m it is paying out. In the early 1980s the tax was as high as 20%.

The Irish Bookmakers Association — which once called for the comptroller and auditor general to run a value-for-money probe into HRI — has successfully lobbied against any move to increase the levy. The bookies argue it is unjust as horse racing accounts for a diminishing share of their revenues. They also warned, before the introduction of the online tax, that higher levies on high-street bookmakers would drive more punters online and lead to shop closures and job losses. The move of betting online proved an unstoppable trend, with 35% of shops closing since 2008.

The state’s contribution to racing prize money attracts little scrutiny. In July 2012, economic consultancy Indecon did conduct a report into “certain aspects” of the horse racing industry. It supported “additional and sustainable funding for the development of the sector”, advising that “this must be accompanied by an equal priority to maximise efficiency, effectiveness and value for money”. It recommended that the Department of Agriculture undertake a value-for-money review of the funding of horse racing “within 18 months”. It never took place.

The sport does at least recognise the need to up its game commercially. HRI chief executive Brian Kavanagh, who has been reappointed for a further five years, welcomed an 8% increase in sponsorship for the first six months of the year, and said the body was working with racecourse owners to draw in more sponsorship for all feature races. Yet the sport is not an easy sell. The make-up of sponsors has changed radically in the past decade. Gone is the near €850,000 that came from the construction sector. Apart from beer companies, the strongest supporters are bloodstock agents, stud farms, racing media and, ironically, bookmakers. John Trainor, managing director of Onside, which specialises in backing for sport, said that racing did not come within the top 10 sporting sponsorship opportunities in its annual survey of Irish corporates.

“Given that one in three Irish adults has an interest in racing at some level, that’s somewhat surprising,” he said.

There are structural issues, admitted Trainor. Races and race meetings tend to be one-offs, and sponsors prefer to support those sports and events that can give them ongoing exposure. “Guinness takes an umbrella approach — it will sponsor Punchestown and Galway, and it has been successful,” said Trainor. “But in general, there are not too many big consumer brands looking at racing.”

Budweiser’s 22-year association with the Irish Derby ended in 2007. Its replacement, Dubai Duty Free, has strong connections with racing but little brand resonance here. It is also chipping less money into the prize pot. In the last year of Budweiser’s involvement, the Curragh annual sponsorship was €2.7m. In 2015, it had fallen to just under €850,000. Trainor, however, believes sponsors could be brought back. “It could take just one brand to start a move back into racing,” he said.

Rails bookmaker Hyland sees an altogether different dynamic emerging in the industry. He believes that, outside of the seven racing festivals which account for almost half of all attendances, the spectator is becoming an irrelevance. The tracks often make more money from media rights — relaying pictures to betting shops and satellite TV channels — than gate receipts. Rights to live racing have been sold to Satellite Information Services, and are believed to be worth about €5,000 per race to courses. HRI receives 20% of the media rights contract.

Hyland attended a meeting at one track last December where the public facilities, including toilets, were closed. “I was told that the public could use the owners’ and trainers’ facilities, which have a sign saying, ‘For owners and trainers only’.

“Why would anybody bother getting off their sofa?” he asks.

HRI has submitted a draft strategic development proposal to the Department of Agriculture setting out “ambitious plans to increase its contribution to the economy”. Perhaps this time the state’s role in funding those plans might get a bit more attention.